- FOREST

- SCA's FORESTS

- WELCOME TO OUR FOREST

- GALTSTRÖM IRONWORKS

- LIFE IN THE IRONWORKS

Life in the ironworks

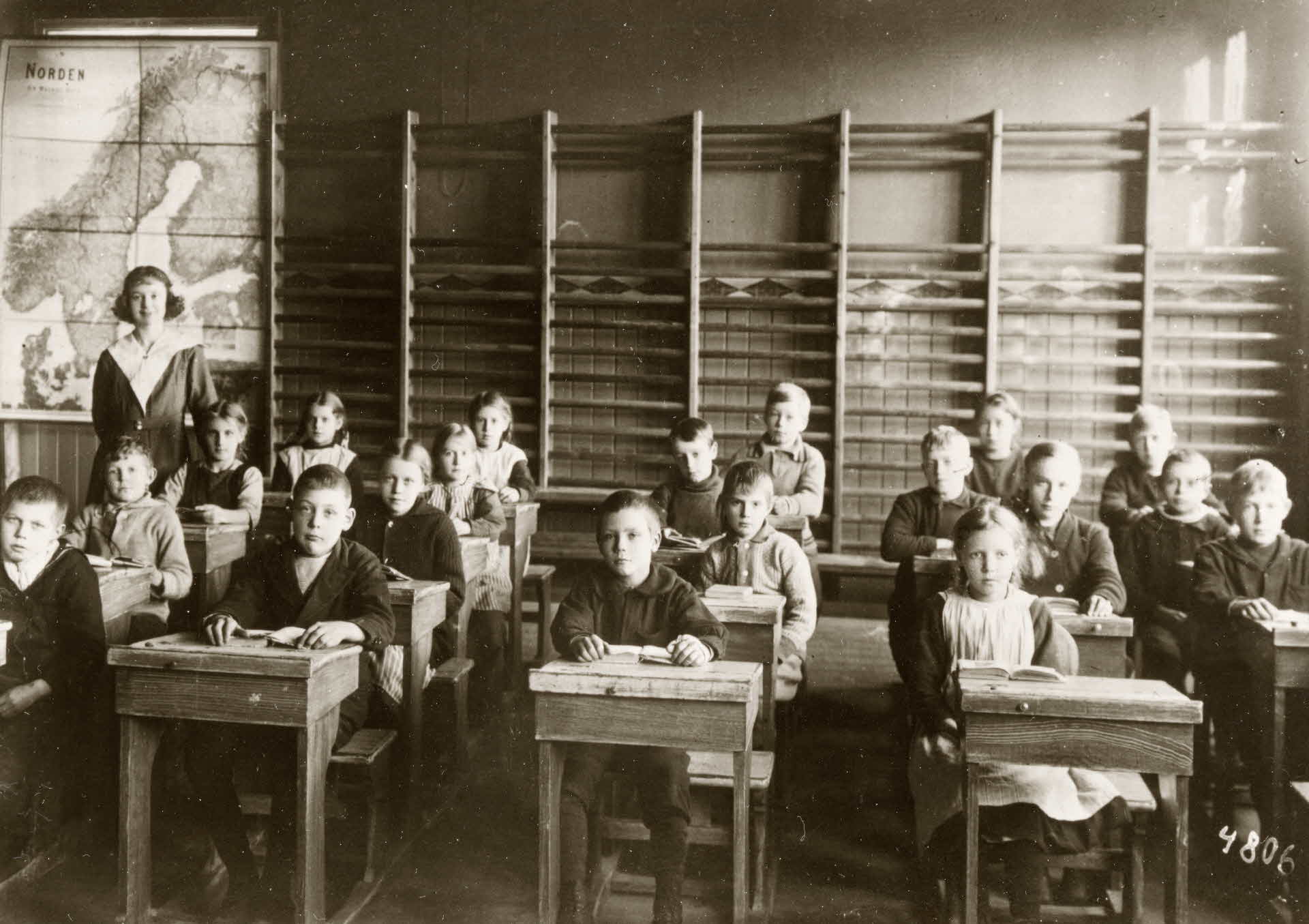

Galtström is an idyllic place today, but when the ironworks were in operation, it was an industrial municipality where the people worked hard. It’s difficult to imagine the working conditions and the work environment at the ironworks during this period.

The manual labor took a heavy toll on the workers’ bodies and the noise of the trip hammers was deafening. Smoke and coal dust attacked their lungs. Some of the work was carried out in unimaginable temperatures. The men often handled iron that was more than 1,000 °C with very little protection. They worked in shifts to keep the works in operation. They had time off between Saturday night and Sunday night or Monday morning.

There were many different trades – crushers, cutters, dressers and charcoal burners. The trades were often passed on from one generation to the next. If a man was a blacksmith, for example, his son would become his apprentice and learn the trade. The workers were local people who came to Galtström for work. When the works opened at the end of the 17th century, Walloons from France and Belgium were employed because they were skilled craftsmen.

Northern Sweden was industrialized in the 19th century. The labor market opened and people flocked to places where they could earn a livelihood. The sawmill communities along the coast grew and became inhabited by people who had previously earned a living from farming. The changes also eventually came to Galtström. Housing for the workers and a farm were built in the mid-19th century. The works received their first store in 1873, in the office wing of the mansion. The workers became organized in trade unions and the sobriety movement. The spirit of the ironworks lived on by virtue.

The ground vibrated in a steady rhythm from the beat of the trip hammers. When the trip hammers were in operation – both the shaft and the head – a set of four hammers worked the iron. In 1877, a mumbling hammer was purchased for the head of the trip hammer at Hammardammen. This type of hammer could weigh up to seven tonnes. The story goes that every time the trip hammer fell, the force was so great that ripples spread across the surface of the dams. When the fish didn’t bite, the fishermen claimed the hammer blows scared the fish all the way over the Bothnian sea to Finland. However, there were similar kinds of ironworks there with the same type of hammer mills.

The women worked on the ironworks’ farm. They toiled with the autumn harvest, milked the cows, worked in the dairy and preserved fish. The women were also responsible for heavy household chores and the children. They cooked, washed, took care of their children, baked and cleaned from dawn to dusk.

Despite their long working days, people in Galtström occasionally had time for fun and leisure. Hunting and fishing were popular pastimes for the workers. In 1880, the first orchestra was put together.

Life in Galtström was strictly regimented and all of the workers were dependent on their employer. The owners of the ironworks also owned the workers’ living quarters and the store where they bought their food. Some of their wages were paid in kind, in the form of food or milk tokens, for example, that could be used in the store to buy food. There was also a form of social security – when the blacksmiths couldn’t work anymore, they were given simpler tasks and women who were widowed received support.